Vitabu Reads | Looking Back - My Life and Times: Dr. Sama Banya

Dr. Sama Banya’s autobiography, Looking Back - My Life and Times, is a great book to read. I found some of the best yarns and anecdotes on “big man politics, African conflicts, and informal power” in contemporary Sierra Leonean history.

Born into a well-oiled machine for warrior-kings, Dr. Banya takes the reader on an epic tour of his hometown, which has seen consequential events in the nation’s 56-year history.

Kailahun district, its 14 chiefdoms—the last level of administrative subdivisions— neighboring districts, and their institutions, have all produced major political players.

Sama, the grandson of Kailondo, one of Kailahun’s most famous warriors, was born in 1930 in Luawa Chiefdom of Kailahun. The town of Kailahun, which means Kai’s town, was named after Kailondo.

Banya’s book has no shortage of information on the seven generations preceding him.

They include incidents such as the duel between Kailondo and Ndawa at Ngiehun in 1890; folklore on why the hunter who kills a leopard is always accused of having slain a king; on the legend of Yigidy waterfall, where Kailondo is said to have slain 200 slaves; on why all his father’s sons were called Sama, meaning “socialite,” and on household names from Segbwema to Daru, Kissi Kama, Kissi Teng’s Kangama, and Kissi Tongi’s Buedu.

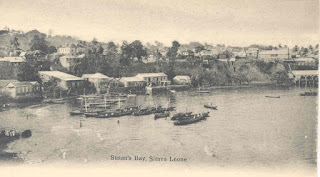

Banya’s book showcases Segbwema, Kailahun district’s largest city, as well as its market towns and garrisons like Koindu, Daru, and Pendembu, the terminus of Sierra Leone’s colonial-era railway.

“Kailondo Square, Luawa chiefdom”

By 1941, Banya’s father, Paramount Chief Momoh Banya, born circa 1880, was on a monthly salary of one hundred pounds sterling.

A kingly sum, considering the principal of Bo School, a storied institution that Sama later attended, was on a thirty-pound sterling a month salary.

Momoh Banya’s Kailahun had about six hundred homes. He was elected regent chief in 1922 and paramount chief in 1924.

Sama described his father as a progressive ruler. He built a dispensary, provided the labor and made cash donations to the construction of a Methodist primary school, the only school in town.

Momoh Banya’s Kailahun had about six hundred homes. He was elected regent chief in 1922 and paramount chief in 1924.

Sama described his father as a progressive ruler. He built a dispensary, provided the labor and made cash donations to the construction of a Methodist primary school, the only school in town.

“His other projects included widening of the road from Pendembu to Kailahun to sixteen feet. He was instrumental in providing free labor for the extension of the road to Dodo Katuma, which was eventually extended to Buedu in the Kissi Tongi Chiefdom.”

The incumbent colonial governor was so impressed by these developments he wished for the D.P.W. to purchase a Ford lorry with spares and send it to the chief as a reward, adding to the chief’s fleet of commercial vehicles that brought him a substantial income.

Sama wrote he had no doubt that if his father was literate the governor would have nominated him Paramount Chief, Member of the Legislative Council and even of the Executive Council.

The current Sierra Leone Parliament owes its origin to colonial constitutional developments dating as far back as to 1863 when attempts were made by the British authorities to put in place Legislative and Executive Councils. The Executive Council was made up of the Governor, the Chief Justice, Queen’s Advocate (Attorney-General), Colony Secretary and the Officer Commanding Troops.

“Important Role Models”

Sama found his father “extraordinarily humble to Europeans,” probably reminded of the way his own father, Kailondo, had been humiliated by the colonial governor of the time.

In 1935, shortly after Sama’s father’s grandmother died, the young boy moved to his mother’s village of Siama to live with his maternal uncle, Musa, who remained an abiding influence in Sama’s life.

Sama’s mother, Kema, had been married to one of his father’s section chiefs and already had two sons before her first husband died. Kema was a singer, and when she delivered Sama she put the happy event in a chorus:

“Here she was, Kema Nguleimoi, adding her own Sama to Momoh Banya’s compound.”

The chief had four categories of wives. There was the head wife, a much younger favorite wife, the chief’s wives, and then there were the elderly wives.

The number of Momoh Banya’s wives continued to increase to his death, Sama wrote. In that era, women were presented as a way to court favor or patronage within the chiefdom. Fellow paramount chiefs also presented their daughters as a mark of friendship.

Away from his father's court and exposed to farming in his mother’s village of Siama, the activities inspired Sama to produce a Farmer’s Calendar, which described the sequence of events in a farming year, beginning with the selection of an area to cultivate and ending with the harvest.

Siama was also where Sama conquered his fear of heights. Crossing a rope bridge over a swollen river was an unforgettable lesson in courage that his Uncle Musa taught him. It was also at his uncle’s house that Sama was circumcised in a clearing one cold, dark morning during the harmattan season.

Sama’s uncle died while he was away in the United Kingdom studying medicine, so he never found out how Musa performed surgery on his patients although “he never sutured wounds, used anesthetics or antibiotics, or anti-tetanus drugs. “

When Sama appeared before the panel for admission at the University of Bristol Medical School he was asked why he wanted to be a medical doctor.

“I saw eyebrows raised in astonishment when I answered that I considered myself lucky to be before them, and went on to tell them that as an infant, I had been force fed by hand, suffered from killer childhood diseases of respiratory infection, diarrhea, measles, whooping cough and worm infestation, and that bilharziasis or schistosoma infestation was also common among us.”

“The Bo School Years”

But long before medical school, Sama’s years at the Bo School, which was founded in 1906 for the sons and nominees of chiefs, were hailed as a seminal period.

In his day, the boarding school ran from mid-February to June 15 and then from the end of June to mid-December.

While there, Sama enjoyed his first ride on a train, with a maximum speed of eighteen miles an hour; joined the scout movement, and was exposed to the natural wonders of a hidden beachhead, which the Sewa River revealed during the dry season.

Sama also fell in love with the wild, and the seeds of environmental protection grew and blossomed into a lifelong interest.

The arrangement at Bo School also ensured that the sons and nominees of chiefs, from chiefdoms and cultures across Sierra Leone, formed a unique band of brothers. Sama learned Themne, in addition to his native Mende; he was also introduced to English cricket, dunked in a pool and forced to swim; and saw his first airplane.

The Second World War stretched its tentacles deep into the hinterland of Africa. However, the death of Sama’s father in December of 1942 was to bring far more upheaval than the war ever had.

After Paramount Chief Momoh Banya was placed in his grave, a few feet away from his own mother, the grave was filled with the symbolic wealth of the chiefdom for the chief’s afterlife: jewelry, cash and a quantity of country cloth.

By the New Year, Sama’s eldest brother, the family’s candidate for the chieftaincy, made it clear he could no longer support all his father’s sons at madras or European mission schools.

Bolstered by scholarships and help from his Uncle Musa, Sama completed Bo School and entered the Prince of Wales (POW) School in Freetown in 1949.

It was at POW that Sama began to take an interest in national politics. Albert Margai, who had served in Kailahun as a nurse, had returned home as a lawyer in 1944.

Margai was elected first Protectorate Member to the Legislative Council in 1951. In 1952, he became a cabinet minister and Sierra Leone's first Minister of Education.

By 1952, Sama was teaching General Science at the Bo school, a year before he left for the United Kingdom.

“Britain was home away from home”

The second half of the book covers life in London and student days at Bristol University. During a short trip home, he paid a visit to government officials like Dr. Milton Margai, and Albert Margai.

Albert served as finance minister in Milton's government after 1962, where he also held positions alternatively in Education, Agriculture, and Natural Resources.

By the summer of 1959, Sama married Juliette Gulama, a health professional, at the Fulham Road Methodist Church. He also acquired his first car, a 1935 Morris, which he nicknamed “Mama Sombo” after his paternal grandmother.

“Britain had been a home way from home,” Sam wrote.

On August 4, 1963, Sama and Juliette sailed on the M.V. Aureol from Merseyside. Ten days later the boat docked at the Queen Elizabeth II Quay and there began weeks of celebration for the new Sierra Leonean medical doctor and his bride, before they took up an appointment at the Bo Government Hospital.

Dr. Sama Banya had entered Bo School in 1940.

Later in his career, the young doctor held progressive positions at Kenema hospital, Njala University College, Segbwema Hospital, Panguama hospital, and Makeni Hospital, where he spent much time in discussions with the ill-fated Ibrahim Taqi, a medical student turned journalist. By 1967, Dr. Banya was a senior medical superintendent in the Ministry of Health.

"There is a section, which deals with a Canadian doctor who worked with young Dr. Banya in his hospital in Kenema in the 1960s," wrote Lans Gberie on a popular Sierra Leonean listserv. Gberie is a senior researcher with the Africa Conflict Prevention Programme of Institute for Security Studies in Addis Ababa.

"The doctor happened to be Jewish -- he was doing volunteer work. Such was the allure of our new Independence that you had many folks from the West, often sponsored by their governments. But sometimes by themselves, coming to our countries to help.

"But this doctor was apparently a little to one side. It was during one of those Arab-Israeli wars. He objected strongly to treating Lebanese patients. Though many were born in Sierra Leone and spoke Arabic with great effort, this doctor insisted that they were Arabs, enemies of the Jewish state. So he refused to treat them. He made a huge drama out of it, according to Dr. Banya's account, even eventually suing the Canadian government for thrusting him in that position!

"It gets more interesting," Gberie continued. "A Sierra Leonean friend of mine in Ottawa borrowed the book, and on reading it, recognized the doctor -- an old man now -- as his friend. He took the book to him (the doctor lives in Ottawa) to the utter embarrassment of the earnest young Jewish nationalist!"

Dr. Sama Banya had entered Bo School in 1940.

Later in his career, the young doctor held progressive positions at Kenema hospital, Njala University College, Segbwema Hospital, Panguama hospital, and Makeni Hospital, where he spent much time in discussions with the ill-fated Ibrahim Taqi, a medical student turned journalist. By 1967, Dr. Banya was a senior medical superintendent in the Ministry of Health.

"There is a section, which deals with a Canadian doctor who worked with young Dr. Banya in his hospital in Kenema in the 1960s," wrote Lans Gberie on a popular Sierra Leonean listserv. Gberie is a senior researcher with the Africa Conflict Prevention Programme of Institute for Security Studies in Addis Ababa.

"The doctor happened to be Jewish -- he was doing volunteer work. Such was the allure of our new Independence that you had many folks from the West, often sponsored by their governments. But sometimes by themselves, coming to our countries to help.

"But this doctor was apparently a little to one side. It was during one of those Arab-Israeli wars. He objected strongly to treating Lebanese patients. Though many were born in Sierra Leone and spoke Arabic with great effort, this doctor insisted that they were Arabs, enemies of the Jewish state. So he refused to treat them. He made a huge drama out of it, according to Dr. Banya's account, even eventually suing the Canadian government for thrusting him in that position!

"It gets more interesting," Gberie continued. "A Sierra Leonean friend of mine in Ottawa borrowed the book, and on reading it, recognized the doctor -- an old man now -- as his friend. He took the book to him (the doctor lives in Ottawa) to the utter embarrassment of the earnest young Jewish nationalist!"

In 1968, Dr. Banya was charged with conspiracy to overthrow the government of Sierra Leone. He was locked up in Mafanta, one of the most notorious prisons in the country.

"Puawui"

After his release, Dr. Banya went into private practice and opened the Nongowa Clinic. 1975 marked a watershed in his personal life.

First, he lost his mother, Mama Kema. It was at the 40th-day ceremony that popular singer and griot, Amie Kallon, called him Puawai, meaning gray hair, in one of her choruses.

Puawui became Sama’s nom de plume ever since.

Sama also lost his wife, Juliette. She succumbed to complications brought on by high blood pressure.

By 1976, Dr. Banya finally responded to the overtures of Siaka Stevens, the third prime minister of Sierra Leone from 1967 to 1971 and the first president of Sierra Leone from 1971 to 1985. Stevens' leadership is often said to have consolidated power by means of corruption and exploitation. (The Heart of the Matter Sierra Leone, Ian Smillie, Lansana Gberie, Ralph Hazleton).

Puawui became Sama’s nom de plume ever since.

Sama also lost his wife, Juliette. She succumbed to complications brought on by high blood pressure.

By 1976, Dr. Banya finally responded to the overtures of Siaka Stevens, the third prime minister of Sierra Leone from 1967 to 1971 and the first president of Sierra Leone from 1971 to 1985. Stevens' leadership is often said to have consolidated power by means of corruption and exploitation. (The Heart of the Matter Sierra Leone, Ian Smillie, Lansana Gberie, Ralph Hazleton).

Dr. Banya also found love again in the mid-1970s. Mrs. Kadi Banya was married to Banya for 40 years before she died of a heart attack on September 4, 2014, the year the first officially confirmed Ebola case was recorded in, Kissi Teng chiefdom, Kailahun District.

Once part of a "new generation" of African professionals in the mid-1960s, Dr. Banya also became one of the "big men" of African politics.

His native Kailahun has seen some of the worst political revolts. Sporadic rebellions continued until March 1991, when the first shots were fired in Bomaru, and the violence spread across the country leaving a trail of destruction.

Miriam Conteh-Morgan, a former African Literature lecturer at Ohio State University, read the book some months ago to enjoy Puawui's writing style.

"I read it more to get insights into a political era, to get details of the machinations and power plays," Conteh-Morgan said, adding that she isn't sure though there was candour all the way.

"But everyone knows the shortcomings of memoirs and autobiographies -- slant, selective memory etc," she said. "It was an interesting walk with him. Should it have been that voluminous? Well, nine decades ain't nine days."

Once part of a "new generation" of African professionals in the mid-1960s, Dr. Banya also became one of the "big men" of African politics.

His native Kailahun has seen some of the worst political revolts. Sporadic rebellions continued until March 1991, when the first shots were fired in Bomaru, and the violence spread across the country leaving a trail of destruction.

Miriam Conteh-Morgan, a former African Literature lecturer at Ohio State University, read the book some months ago to enjoy Puawui's writing style.

"I read it more to get insights into a political era, to get details of the machinations and power plays," Conteh-Morgan said, adding that she isn't sure though there was candour all the way.

"But everyone knows the shortcomings of memoirs and autobiographies -- slant, selective memory etc," she said. "It was an interesting walk with him. Should it have been that voluminous? Well, nine decades ain't nine days."

Looking Back - My Life and Times Paperback by Dr. Sama Banya

Product Details

Paperback: 486 pages

Publisher: Sierra Leonean Writers Series (SLWS) (February 25, 2015)

Paperback: 486 pages

Publisher: Sierra Leonean Writers Series (SLWS) (February 25, 2015)

Comments

Post a Comment