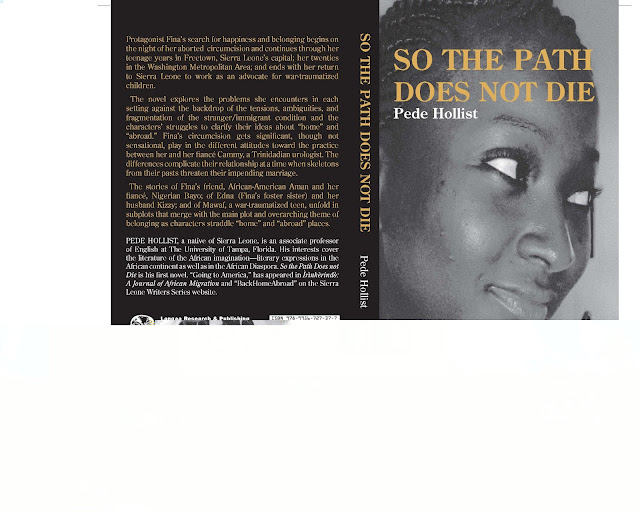

Kadiatu by Harriet Yeanoh Jones

Harriet

Yeanoh Jones is a lecturer at the Institute of Languages and Cultural Studies, Njala University, Sierra Leone.

When Mum came back home that evening, she was greeted by the sight of a little girl coiled up in one the armchairs in the sitting room. She was fast asleep, and looked somehow knackered.

“She is indeed tired,” remarked her uncle who had been waiting

patiently to formally present her young stranger to Mum. "She’d never

stepped out of her village before and besides, this is the longest journey she

has ever made,” he continued.

“What’s her name?” Mum asked.

“Kadiatu,” he replied. “Kadiatu Isatu Kamara.”

As Mum continued asking about other personal details, she

carefully perused the little girl’s face. It looked unattractive to her- a dark

skinned girl, about the age, ten or younger, with short black hair.

After

having taken in some details, it was as if Mum had said to herself, “I am

going to have her all to myself. There’s plenty of time for me to study her

physical as well as every other bit of her makeup.”

“How old is she?” Mum asked eyes still feasting on the girl's

visible features.

“I am not certain,” the uncle replied, “However, I shall try to

get that detail from her father as soon as possible,” wiping the sweat that had

begun to form on his forehead with the back of his left hand.

Mum went on to ask whether Kadiatu had a birth certificate. It

was at that point that she learnt that Kadiatu’s father was a primary school

teacher in the village, and therefore could not afford to treat such matters

with levity. Ali, for that was the uncle’s name, promised faithfully that he

would go back to the village as soon as he could to collect the birth

certificate from Kadiatu’s father. Mum was not surprised to learn that Kadiatu

was already enrolled in school, and that she was in class three, given the fact

that the father was not only an educated man, but also one who was occupied

with the business of imparting knowledge to children in the community.

Uncle Ali left shortly after Kadiatu had gone to bed, and he

himself was satisfied that he had answered the questions that required

immediate responses. That first night Kadiatu slept like a log. By 6 o’clock

the next morning, she was up. Mum showed her the bathroom, as she definitely

needed to sort herself out. Mum watched with keen interest as the little girl

painstakingly washed various parts of her body in preparation for prayers. This

was something she had obviously learnt from her parents.

“Kadiatu, you needn’t

do all of that anymore. You are now in a different environment,” Mum said, now

eased off.

After she left the bathroom, Kadiatu wanted to say good morning

to Mum and Dad. How could she? She could only speak Themne, which no one else

in the household understood; every other person in the household spoke Krio, a

language that was completely strange to her. That barrier remained a problem

for weeks. It was a constraint on the one hand for the family and a source of

frustration on the other for Kadiatu. She could neither interact verbally nor

could the family interact with her. The other little girls, her age, also found

it somewhat difficult to interact with her. Whenever they spoke to her, she

just stared vaguely at them.

Apart from the frustration Kadiatu was battling with,

she was also missing her parents, siblings, playmates, and other people with

whom she used to speak. Now it was all so strange, Kadiatu thought.

Indeed,

back in the village there was a lot of work but though her life and that of the

other villagers were finely spiced up with some kind of incomprehensible bliss:

going to the stream with the elders and other children to fish or fetch water;

going to the farm in the early hours of the morning to weed or scare birds; not

having much to do in harvest festivities or in the preparation of the late

evening meals, it was better for Kadiatu than this cage of luxury in which she

had found herself. The effect it had on her was quite tremendous.

As the days went by and things continued to unfold, Mum became a

bit baffled. She found it hard to figure out how a child who had absolutely no

knowledge of English could be in class three. As a matter of fact, the

prescribed texts were all written in English.

She had many doubts about this

young girl for which she needed clarification. What shocked Mum even the more

was that there were certain schools in the remote parts of Sierra Leone that

were not following the prescribed government calendar: community life or nature

dictated.

For instance, whenever there was a bountiful harvest, school could be

closed temporarily as both teachers and pupils had to be involved in farm

activities. For these people, school was not much perceived as a means of

empowerment. After all they were leading happy lives without schools. Such was

the life led by Kadiatu in the village. As Mum got to understand these peculiarities,

her state of bafflement gradually disappeared.

A New Family

In the Moyamba district, Southern province of Sierra Leone,

there was a small village called Mochail, Kadiatu's birthplace. There she lived in

a small hut with her parents, five siblings, uncles, aunts, and grandparents;

sheep and chickens with which they shared the hut not counted. But they were

happy. This union Kadiatu missed very much.

“Kadiatu, you are going to Freetown, a very big city where a

better life awaits you,” her father told her.

“Your uncle has met someone loving who has promised to take good

care of you.”

Kadiatu was saddened by the news. She did not want to leave her

parents, siblings and friends but her father's dictates were to be followed no

matter what. Besides, her father told her Uncle Ali himself lived in Freetown

and would be checking on her from time to time, she felt a bit assured of

security.

Isatu Kamara, Kadiatu’s mother was not very pleased to see her

young daughter go to such a big and dangerous city but the promise of a better

life and the hope of a secured future made her to let the child go, even though

reluctantly.

So they went to consult the “medicine man”. In this community,

religious and traditional leaders were highly revered; therefore whatever

utterances made by them were always treated with utmost seriousness. When the

'medicine man' predicted of a brighter future, Kadiatu's mother no longer

haboured any hesitation to let her daughter go to the big city.

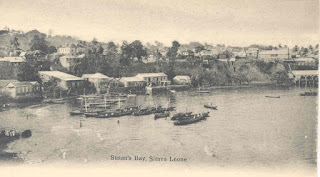

Kadiatu with her uncle left the seaside village of Mochail on a

Sunday for the capital city of Sierra Leone.

They travelled by boat and arrived

at Fogbo. At Fogbo they boarded a vehicle for Waterloo. When they got to

Waterloo, they boarded another vehicle, which took them into the heart of the

city of Freetown.

Indeed, it was all strange for Kadiatu. She found herself

strapped in a maze of big and beautiful buildings compared to the tiny huts in

the village. But their house had few people and they were Christians. She,

coming from a strongly rooted Islam community, found it difficult to follow the

Christian life. Education was viewed as key to life’s success. Nearly every

other aspect was differently done in both communities.

At first it appeared as if Kadiatu would never cope.

She cried

for days on end. One day Mum almost sent her back to the village but she called

Uncle Ali and told him about Kadiatu’s difficulty in settling down. On one

occasion, Kadiatu took the black plastic bag she had brought along with her

from the village and attempted to run away but was caught by a neighbour,

Michael, who told her that she would be eaten up by cannibals if she did not go

back home. It was that threat that made her run back home.

Mum found the

situation a bit disheartening; she had done all she could to get Kadiatu

integrated, all to no avail. Kadiatu still wanted to go back to the village and

stayed isolated from the other children from time to time singing Themne songs.

No matter what Mum did, she could clearly recall one common expression: “Mine I

yema kone do mama” meaning she wanted to go to her mother.

What Mum found interesting in all of this was the fact that

Kadiatu would consume every bit of food she was given then continued with her

crying interspersed with singing. She never for once rejected anything she was

offered to eat or drink.

When Kadiatu heard the message from her father that

she never was going back to the village, she realised with frustration that she

was in the city for good and gradually changed her attitude. She began to note

the beautiful things, which were absent in her village.

Adaptation

As days, weeks and months went by, Kadiatu began to feel at ease

in her new environment. They began to have much of fun and

laughter. There were happy moments, interesting moments and even sour moments.

As she acquired the lingua franca, she became livelier in her interactions with

one and all. A great impediment to her social life had gradually

disappeared-the language barrier.

She could confidently communicate with

everyone around. She apparently found joy and happiness in this her new family.

But certain dishes still posed difficulties to Kadiatu, for she was not used to

eating salad, which for her was merely a combination of uncooked leaves. However,

with time she grew to like them even better than the African dishes she had

been used to.

Mum could vividly recall when she once said to her, ”Mama, we are

going to prepare Jollof rice, don’t forget to buy the vegetables to garnish

it.” Mum could not help but laugh. Mum said to her, ”You seem to like

vegetables more than everyone else.”

“Yes, I really like vegetables especially cabbage and carrot,”

she answered with a broad grin.

Sunday after Sunday, Kadiatu would be so excited to dress up in

her fineries to go to church. She was completely adapted. Once, when she was in

a lighthearted mood, she said to Mum, “I enjoy singing hymns. I find them soul

refreshing. That is one of the reasons why I like orthodox churches.”

Initially, Mum thought she had gone too far but when she sought

the consent of Kadiatu’s parents on the issue of going to church she was relieved

to know that they were not worried about the change. As far as they were

concerned, Kadiatu’s general wellbeing superseded all other matters, even

extending to that of religion.

In all this, there were happy and interesting moments and there

were sour or not so pleasant moments. Kadiatu had started school, a stone’s

throw away from her new home. She was admitted into class two. Mum

suggested that Kadiatu should be placed in class two because she had a rather

weak foundation. Even in class three, the class she was in in her village

school, she could neither write properly all the letters of the alphabet, nor

could she sound them. Writing figures one to twenty was a task that equally

posed difficulty.

That was why Mum was really taken aback and she became angry

when she learnt from one of her nieces in the same school as Kadiatu that she

stoutly refused to stand with the other class two children during morning

devotion but would rather join the class three children. She would tell

them that she belonged to class three and therefore would never stand with

them. It was after some warning and counselling from Mum that she agreed to

stand with the class two children during devotion.

In Kadiatu’s new family,

study time was a daily activity. Every child had to study for at least an hour

or two. This was an experience that Kadiatu found most undesirable. She would

grumble, frown and even shed tears whenever it was study time.

Once, she was

even bold enough to say that she wasn’t going to do the exercises assigned to

her. She was not used to this kind of rigorous training. For her, study time

meant looking at pictures and flipping through the pages of books. But things

were not going to change so she eventually succumbed to them.

On certain evenings, when Kadiatu was in high spirits, she would

narrate some interesting incidents or general happenings of her village. The

amazing part of it was that she would even condemn certain things she had been

enjoying or of which she had been a part. The ideal was what she now saw in her

environment. For instance, here cassava leaves was not pounded but done by a

machine. Tasks were carried out here less laboriously. To her, things were much

more impressive in the city. There were big shops and supermarkets all over the

place.

In school, Kadiatu was an average pupil; a persevering learner

who was loved by all her teachers. She had grown to be civil and neat. Whenever

children of her age and perhaps some a bit older came around, she would raise

the bed covering which usually drapes over the bed to display her collection of

footwear. That was her subtle way of showing off. At the uppermost level of her

primary school career, she became one of the fond girls of her teachers. Of

course this was something she never told Mum about.

With the regular supervision, she received at home and the

teaching in school, Kadiatu did fairly well at the National Primary School

Examination (NPSE), and she was admitted into the Freetown Secondary School for

Girls (FSSG). There again, because of her pleasant disposition, she was loved

by her teachers and friends. Kadiatu continued working hard; when she took the

Basic Education Certificate Examination (BECE) she was admitted into the senior

section of FSSG.

Kadiatu had grown into a beautiful young lady; tall and dark

with black hair and bulging eyes, and she still loved to dress well. In the

evenings, she would take her second bath and dress up in clean clothes. After

finishing her chores for the day, she would pick up her books to study, and she

would go on until she finally falls asleep. She also found time to

relax-watching movies. From time to time she would sit with her peers and

together they would discuss topics of interest.

Five years after Kadiatu joined her new family, a new member was

added, a baby brother. Kadiatu’s love for her baby brother was so great. In

fact, both of them were fond of each other. They would hug and played with each

other. One can actually see that they enjoy each other’s company in spite of

the age difference; just one the reasons Mum thought of Kadiatu a perfect

girl. She (Mum) was considered impatient and very intolerant but Kadiatu was

always full of praises. I

n any case, Harry and Kadiatu’s relationship could be

compared to that of “Mary and the Little Lamb.” Kadiatu had a sister also with

whom she shared company; the one who had been around before Harry was born. Mum

was that sister.

Naturally, Harry and Kadiatu would quarrel every now and

then over nothing. Sometimes they refused to speak to each other but Mum would always

intervene and keep things in check. In spite of all that, their

relationship was unparalleled. When school choice forced Henry to relocate

in the provinces, Kadiatu could not resist shedding tears. But things soon

became normal. She was happy in her new family, and she coped splendidly. The

hub of the family, she was fun to be with; full of humour, telling little jokes

that made everyone wriggle with laughter.

A Sad Day

One evening, Uncle Ali came on one of his regular visits.

Apparently, he had just come back from the village. He brought with him two fat

cocks and a gallon of palm oil. These were gifts sent by Kadiatu’s mother as a

token of her appreciation.

Uncle Ali told Mum that both parents sent their

warmest regards, and that they were very pleased with the feedback they were

receiving in relation to Kadiatu’s wellbeing. Of course, Uncle Ali gave them

regular update. After all the pleasantries, Uncle Ali sat for a while before

finally dropping the bombshell!

“Kadiatu’s parents sent me to seek permission that together with

her peers she could be initiated into the Bundo society.”

“It’s really not a bad idea,” Mum replied thoughtfully. “The

only problem here is that I would have loved them to wait until she at least

she takes the BECE.”

Mum emphasized she was not imposing her own idea but merely

making a suggestion. That was the message Mum asked Uncle Ali to take back to

Kadiatu’s parents. In a very calm manner, Uncle Ali responded that he’d do just

as Mum had requested. Kadiatu was not present when that discussion between Mum

and Uncle Ali took place.

After Uncle Ali had gone Mum called her and informed

her about her parents’ wish. Before Mum finished the explanation, Kadiatu burst

into tears. Not that she had a problem with the initiation ceremony; in fact

she hadn’t the faintest idea as to what it really involved. As far as she was

concerned, it was merely fun and enjoyment. It was a time for dressing up in

fineries and receiving special treatment.

All of that was quite all right. What

saddened her was the fact that she was going back to the village. In her little

mind, she thought perhaps she would not be coming back to the city. She feared

she might be given in marriage to an older man in the village, and that she

would eventually drop out of school.

Mum was really surprised. She sat

speechless looking at Kadiatu as she sobbed. After a few minutes, Mum told her

to calm down and listen. Mum then told her what she had told Uncle Ali.

“As it

stands we are waiting for their response to my suggestion, and I am convinced

we’ll get a positive one,” Mum assured her. “Stop doing this to you” Mum

continued.

After some intermittent outbursts she finally kept quiet. Even

though she had stopped crying she was in a sombre mood for the rest of the day.

She could not laugh; she could not play like she used to, and on that

particular day she retired early to her bed. She might have even dreamt about

everything that happened on that day especially when her fate was yet

undecided.

A Ray of Hope

Two weeks on, Uncle Ali came back from the village. His presence

created anxiety in Kadiatu. What could her parents have said in response? Would

she really be going to the village? Did her parents give Mum’s suggestion a

serious thought? But they had given her to this family and she had agreed to be

a member. What ever be the case, her new family's say should be final.

Such

were the thoughts pricking her mind. She could neither sit down nor stay in one

place. She kept pacing up and down under the pretext of doing some work, but

she meant to eavesdrop. Her heart throbbed so hard.

Uncle Ali sat in a rather relaxed manner, his face lightened up

with a smile. He talked about quite a few things but none had to do with

Kadiatu. Mum didn’t want to jump the gun, so she waited patiently as the

conversation continued. Finally Uncle Ali came out with it.

“The young lady’s parents think your suggestion is a good one

and have therefore consented to defer Kadiatu’s initiation to a later date. Mum

jumped and immediately called Kadiatu to share the glad tidings with her.

Kadiatu’s face lit up with joy. She was more than pleased with what she heard.

Once again she became buoyant. She knew she’d definitely have to go to the

village in due course, if not for anything, but to bond with her parents and

siblings. Mum equally wanted Kadiatu to understand she had an identity, and

therefore must not run away from her roots. That was something very serious for

Mum; the reason why she always consulted Kadiatu’s parents on sensitive

issues.

Kadiatu's determination multiplied; determined to succeed in

life, looking into the future with hope.

Kadiatu would soon face the WASSCE. She hoped to become a nurse.

With fingers crossed, the family viewed the beaming light

…

Harriet Yeanoh Jones is a lecturer at the Institute of Languages and Cultural Studies, Njala University.

Comments

Post a Comment