On Eldred Jones’s Freetown Bond by Lansana Gberie

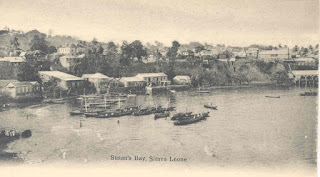

Just down from university sometime in 1994, I went to interview Professor Eldred Jones at his home for a newspaper. A nasty bush war had been raging in the countryside, but Freetown was untouched. At Fourah Bah College (FBC), however, the war had some immediacy. Shortly after it started, several students from the university who had gone on holidays to their villages in the countryside had been abducted by the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) rebels, and those who escaped returned with graphic stories of atrocities.

A coup had occurred, and the youthful soldiers who constituted what they were pleased to call National Provisional Ruling Council (NPRC) were in the habit of frequenting the college’s campus, the appearance of support from the famous school adding some glamour to the ‘revolution’. Jones, the universally venerated long-term principal of the university, was retired to his home at Leicester, at the tip of the Mount Aureol, where the university is elegantly situated. Surely, I thought, the great man would have something to say about the war?

I had met him earlier at one of the cultural events at the home of Karl Prinz, the immensely well-respected German ambassador and patron of intellectuals and local artists, so he had agreed to the interview when I telephoned him. There wasn’t much he would say about the war, however, since “it is very difficult to deal with some of these amorphous groups now emerging here and there in Africa”, he said. Professor Jones had been blind for many years, and he wasn’t known to express political opinions. Probably Sierra Leone’s most admirable academic, a much beloved lecturer and internationally famous literary critic, his great passion remained scholarship and the academia. He spoke with great fondness of his time as principal of FBC, and of his continuing work on African literature, editing the premier journal African Literature Today.

The profile-interview, bland and laudatory, ran a few days later. The following day, Professor Jones, as usual driven by his wife, came to our office on Pademba Road in Freetown, and handed me a small envelop. The note enclosed thanked me for a well-written report, but there was a complaint. The mysterious woman I had referred to in the article wasn’t his wife: his wife was called Marjorie not Margaret, as I had written. It was a devastating reproach; and, full of shame, I got my editors to run a correction in the next edition.

Freetown Bond: A Life Under Two Flags, Jones’ luminous and delightful memoir adds, for me, an extra, retrospective, weight to my foolish mistake in misidentifying Mrs. Marjorie Jones. Perhaps conditioned by his almost-Victorian upbringing, Jones typically treats the issue with a (sort of) English reticence, never sentimentalizing or romanticizing it; but if it has any meaning, the phrase ‘better half’, often bandied about carelessly, is a perfectly etched description of the relationship between Mrs. Jones and her husband. She has been Jones’ friend, lover, partner and wife – as well as amanuensis and inseparable companion – for almost all his adult life. They had met at university during World War II, and got married in 1952. Marjorie and her husband co-founded African Literature Today in 1968 and co-edited it for decades. This memoir, and that admirable journal, would not have been brought to us without Marjorie.

The memoir has a little more to say about the war for which I had dashed to speak to Professor Jones, which would later engulf the entire country, including Freetown, and even Jones’ once-cloistered neighbourhood of Leicester Peak was occupied by foraging thugs called ‘rebels’. Jones found himself, against all his instinct, having to play a (sort of) political role, though even with this clearly traumatic experience, the recollection is made with mordant humour and self-deprecation.

Professor Jones is now almost 90; he turned 89 in January. The memoir shows what an interesting, rich, and immensely satisfactory life this very humane and civilized man, the nearest thing to the scholar par excellence that Sierra Leone has produced, has lived.

Two Flags

The title of the memoir refers both to Jones’ dual heritage as Creole (culturally English as well as African) and one of his lifelong intellectual preoccupations: a very deep scholarly interest in this inheritance and the cultural stew of Freetown in which he grew. Born in the British-ruled Sierra Leone, Jones rose to eminence, as one of Africa’s foremost academics and cultural evangelisers, in independent Sierra Leone. Though very much English in his education, Jones remained firmly rooted in his Creole cultural heritage, which itself is a form of dualism, a condition of hybridity. Postcolonialist intellectuals of a quite different hue and capability, expressing new anxieties, long saw in the Creole evidence of rootlessness and schizophrenia. It is the kind of vanity that never appealed to Jones.

He has remained throughout his long and immensely successful academic career, though deeply appreciative of the new literature from Africa, unaffected by those wonderful fads of academe (post-colonialism, post-structuralism). One gets a clue from the memoir how this remarkable poise was achieved on page 45. Here Jones writes: “I have always been content to live and work in Sierra Leone. A reasonably happy childhood, an easy transition from school and college to work, further study, more work, travel, all was undertaken with Freetown as a tethering post. I was always attached.” Academic success seems to have come to Jones easily: after Oxford, he rather effortless got hired as a lecturer at Fourah Bay College, and his rise in that institution was steady. His work on Elizabethan and Jacobean drama, and particularly his pioneering role in promoting the new African literature through his critical articles, mostly published in the exalted African Literature Today, made him an international academic star, coveted as a visiting professor in Europe, the US and Canada. “Everywhere I went,” he writes, I received flattering offers to take on more permanent appointments…My standard response was a polite ‘no’ in view of my commitment to Fourah Bay College.” The result of this is that Jones is unique among academics in lacking throughout his career the great anxiety to publish, to get tenure, to be invited to conferences, to be cited by peers. When he returned to FBC as a lecturer in 1953 armed with a BA honours from Oxford, Jones had no intention of pursuing a PhD, but a British colleague convinced him that a PhD was “fast becoming a union card” in academe, and so he went for it. He secured his PhD from Durham University in 1962; and he published his first book in 1965.

This memoir, like all of Jones’ published work, is as a consequence completely free of the unpleasing asperity into which disagreements among academics often descend, to the negation of their cause.

Urbane and at home in Africa as in Europe, Jones very early took a deep interest in his native Krio language. It is of interest to learn from this memoir that the Krio language was the subject of Jones’ dissertation for his diploma in education in 1949, after his BA from Fourah Bay College (part of University of Durham at the time). Jones would subsequently gain admission at Oxford’s Corpus Christi College, where he earned an honours degree in English, pursuing his interest in Elizabethan literature, especially Shakespeare. He maintained these two interests – Krio and Shakespeare – throughout his career, publishing the award-winning Othello’s Countrymen (an original study of the depiction of Africa in English renaissance literature) in 1965, and a shorter study, The Elizabethan Image of Africa, in 1971.

After these two books, Jones focused on the extraordinarily interesting literature pouring forth from Africa, and, of course, on his lifelong interest in the Krio language, co-authoring, with Clifford N. Fyle, A Krio-English Dictionary in 1980. He took a particular interest in Wole Soyinka, becoming the Nigerian writer’s most exalted literary champion until Soyinka won the Nobel Prize in 1986. Jones wrote a booklength study, The Writing of Wole Soyinka, published in 1988, and took to referring to Soyinka as “WS Our WS” (Wole Soyinka Our William Shakespeare). Soyinka’s turgid and opaque prose in The Interpreters (his, thankfully, only novel) did indeed need a dedicated champion; and since the Nobel he has focused, in the tradition of creatively exhausted artists, on political pamphleteering, year after year issuing book after unreadable book about the horrors of his country’s dysfunction. (I write as someone whose preference is Achebe, a finer much greater writer).

Fourah Bay College

Jones became a student at Fourah Bay Collge in 1944, and has remained committed, in different forms, to the university since then. The most valuable part of this memoir is Jones’ reflections on his time as principal of the college: it is by far the best account I have read of the decline of the college as a centre of excellence. Jones was principal for eleven years (longer than any other principal before him except the African-American Edward Jones, 1840-1859) from the turbulent 1970s to the meltdown in the 1980s (he retired, almost completely blind, in 1985), by which time Fourah Bay College was now issuing its own, rather than Durham University’s, degrees.

He gives three reasons for FBC’s decline: the expansion of the student population without a corresponding increase in its financial and other resources; the frivolity and foolishness of students; and the depraved national politics of Siaka Stevens. The expansion of the student population caused, first and foremost, accommodation and related problems. A recurrent problem, Jones writes, was the administration of corporate student finances; followed by food and other conditions of residence. The shortage of campus accommodation for students led to enforced non-residence, and this in turn resulted in transport problems. The management of these problems was not helped by the irresponsibility of students. Jones writes:”During the 1950s and 1960s Sierra Leonean students who qualified for entry…got covered… with full board, a book allowance and other college fees. The book allowance was paid to the college, which issued vouchers exchangeable at the college bookshop – which was one of the finest bookshops in West Africa, managed by Hans Zell. Students in the 1970s started agitating that this allowance should be issued to them directly; the college submitted, since this had become a major source of friction.”Now paid directly to the students, the allowance, as any minimally discerning person would have foreseen, was now no longer used to buy books, and the bookshop’s capital base collapsed. It ceased to exist – a valuable intellectual and cultural resource lost forever.

Here’s another: “A similar assertion of rights turned the dining halls into canteens with boarding grants going direct to students – making it easy for the scholarship to be eliminated altogether,” Jones laments. Another primitive assertion of rights had to with the objection to the introduction of foundation year courses, which Jones promoted, incorporating courses in languages, literature, the sciences, history. Meting strong resistance the programme became ineffective. Jones writes in rue: “Our societies in the developing world are still held back by strong residues of traditional thinking which impedes progressive approaches to problems. Logic is held back by belief in magical and occult manipulations which, in turn, perpetuate a reluctance or even inability to pursue truth in scientific as well as in more general matters. Unless we are able to induce a more enterprising, a more adventurous attitude in our educated citizens, we will be condemned to be mere imitators even in the solution of our own particular problems”. (p.74)

I would add to this very wise observation that most of the students going to university were the first from their families to be so privileged, and that there was no culture of book reading in their homes, nothing to augment the courses they take at university. This lack of a broader pedagogical canvass was almost certainly one of the reasons for the persistent student nihilism that Jones had to deal with. A striking one had to do with one Ali Kabba.

Kabba was a student leader in the early 1980s driven by what Jones calls Gaddafi’s “more exotic influence” in the form of the Green Book. Kabba’s application of the confusions of the self-serving and almost illiterate ruminations of that book took the form of feverish juevenile outrages, including the flogging of other students. Jones writes that this “was not tolerated by the college and in due course, the Libyan Colonel’s direct influence on student affairs faded.” It didn’t, really: it only took on a more covert and more sinister form: it was the key element creating the civil war of the 1990s.

An earlier expression of student unrest, a more spontaneous rhetorical gesture, had also triggered an unhappy outcome: the 1977 students demonstration led directly first to the vandalisation of FBC and the beating up and rape of students by President Siaka Stevens’ thugs, and then to the imposition of a one-party state. Jones was principal during both these events, and he almost became a victim in the first. The students had rained insults on Stevens as began his speech as chancellor at convocation on campus but he calmly continued. When it came Jones’ turn to speak, he began by apologizing to Stevens for his students’ rudeness. This later struck the wily Stevens as odd: Jones was apparently reading from a speech, which could only mean – Stevens thought – that he had known about the insults prior to the event. Later that evening, as thugs beat up students, a call came to Jones from the government demanding a copy of the speech. Of course, the apology was never there; it had been an off-the-cuff statement. But well-wishers, more politically attuned that Jones, had advised Jones to take cover, which he did just in time: there were APC thugs looking for him.

Could a good foundation course at FBC be instructive to the students to be better able to understand their options in their world than these futile gestures? If they had read Turgenev and Conrad and Shaw and Camus, they would have recognized worlds similar to theirs – corrupt, oppressive, dominated by a few – but also a warning about the simplicities of revolution and the futility of nihilistic gestures. Instead, on their own they read Fanon and Mao and Che and Gaddafi, and did not read those other writers: that added reading could have struck a note of balance between the tendency towards nihilism and a check on fatalism. Surely, if Kabba had had read Shaw, he would have been careful about recruiting someone like Foday Sankoh into a revolutionary project: he would have known that revolution attracts not just those to whom the world is not good enough but also those who are not good enough for the world.

The point is that university students – whose social position are by definition transitory but very much aligned to those of the ruling classes – cannot lead revolution; very likely they end up being “useful idiots” – the phrase is allegedly Lenin’s – (or worse) of the ruthless sociopaths who ultimately wield control. Mengistu in Ethiopia physically eliminated most of the student leaders who had been his allies, and Sankoh, a homicidal voluptuary, wiped out, in one purge, the people that amounted to the intellectual driving force behind the RUF. They, like Sankoh, may not have been aware of this, but their approach to politics faithfully reflected those of their enemies: it was a version of the scum politics that Stevens had introduced: politics driven by the idea that the hoped-for change, the reality of political success, will come when one simply eliminates the ‘right’ people. Without solid, well-worked out ideas and a concrete political programme, you target enemies, people, for only they are real. That leads, of course, to purposeless violence and destruction driven purely by simple rejection and rage.

Jones’ Legacy

Jones’s legacy as a teacher will remain the gold standard in Sierra Leone: his former students universally revere him, and many of them are highly successful. But younger scholars more influenced by the academic fashions of the 1960s and 1970s have not shared his apparent over-reverence for the English renaissance classics and even Creole culture. Lemuel Johnson, a fellow Creole literary scholar and poet, may be one such. To begin with, Johnson’s depiction of the Creole personality (in The Devil, The Gargoyle, and The Buffoon: The Negro as Metaphor in Western Literature 1969) as “schizophrenic dualism” with “an exaggerated inability to develop a sense of equilibrium between [the] African and English experiences,” is sharply at odds with Jones’ views. Jones finely articulated his views on Creole identity in a 1968 essay: Those who are part of the Creole society, he wrote, “as they celebrate their weddings with gumbe music or dance in evening dress to the strains of western-style bands, or talk to their dead during an awujo feast, or sing Bach in the choir on Sundays, seem quite unaware of their ‘rootlessness’, and display a surprising self-confidence”. The essay is found in Freetown: A Symposium, which Jones co-edited with the pioneering historian of Sierra Leone Christopher Fyfe).

In his Shakespeare in Africa (and other Venues): Import and Appropriation of Culture (1998), Johnson mocks that “rummaging among other people’s marginalia and parentheses” to discover, for example, that Christopher Columbus actually mentioned Sierra Leone in his accounts of his journeys… Ah, he writes, “it is true that those among us who read long and irrelevantly in the endnotes and footnotes of our imperial curriculum did make a point of revealing that their excursions made for startling recognitions. They said, for example, that in those ‘under-cellars’ of our colonial library even Sierra Leone was now and then mentioned…” Though Johnson does not mention Jones or his book, the inference can be drawn.

What about the 418-page Krio-English dictionary? The tome, perhaps influenced by a radical reinterpretation of Creole history by the historian Akintola Wyse, claims that Krio is a West African language which has adapted “even its English and European borrowings into the mould of other West African languages, particularly the Kwa language group to which Yoruba belongs.” The dictionary is a landmark cultural and intellectual achievement, but its argument is not settled; I myself remain a little unconvinced. In a 1962 paper entitled “Mid-Nineteenth Century Evidences of a Sierra Leone Patois,” published in Sierra Leone Language Review, Jones demonstrated how the introduction of Yoruba-speaking Liberated Africans to the Sierra Leone colony in the nineteenth century may have significantly changed the early patois spoken in the colony, leading to the development of the Krio language as it is spoken today. But in this paper, as in the dictionary, one does not get a sense of process over time. The point is that Krio as a language in its early beginnings right into the twentieth century was not the language of the Creole elite; it was a subaltern language, purely oral and protean, and was therefore despised as patios or ‘broken English’. In the nineteenth century it wasn’t spoken, or it being spoken was actively discouraged, in educated Creole homes. (In contrast, Afrikaans, with origins very similar to Krio, was early embraced as a nationalist rallying point by the descendants of Dutch settlers in South Africa, helping it to develop an impressive literature and ensuring its primacy in the country for decades as the official language.). Edward Blyden, a refugee from Liberia, with his cultivated and alert foreign ears and eyes, first recognized its peculiar merit; and he described Krio in 1884 as the “speech of the Sierra Leone streets”. The slightly revanchist celebration of Krio as indigenous is perhaps a welcome embrace of the majority poor, non-elite Creole culture; but this point ought to be made more clearly.

But this is merely carping: the achievement is marvelous, and it can be built upon. This will be a fitting tribute to a great man who dedicated his long life to the work. Salute Professor Jones!

Dr. Lansana Gberie has written extensively on conflict, conflict management, human rights and peacebuilding in Africa, including, most recently (as editor) Rescuing a Fragile State: Sierra Leone 2002-2008 (Wilfrid Laurier Unievrsity Press 2009). He is also author of A Dirty War in West Africa: The RUF and the Destruction of Sierra Leone (London: Hurst 2005). Dr. Gberie was awarded the 'Outstanding Research Award' by the Canadian government body IDRC in 2002 for his work with Partnership Africa Canada on the Human Security and International Diamond Trade project; he and his colleagues were also nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by three senior US lawmakers for this work the following year.

Hardcover: 188 pages

Publisher: James Currey (November 15, 2012)

ISBN-10: 1847010555

ISBN-13: 978-1847010551

The Freetown Bond

Comments

Post a Comment