Summer hangout with Pede Hollist's So the Path Does Not Die

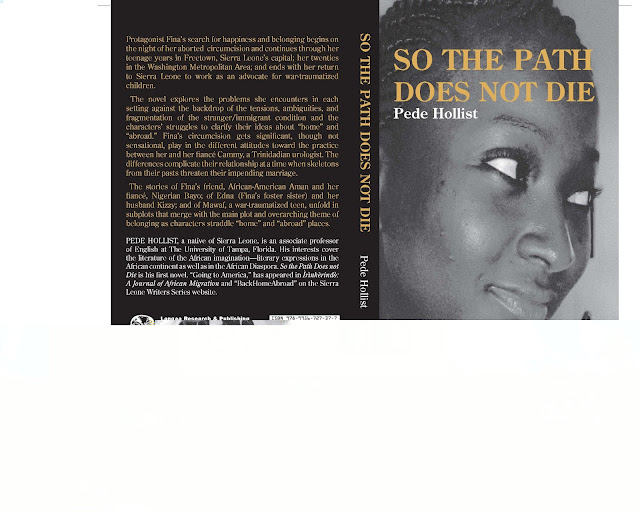

Pede Hollist, a native of Sierra Leone, is an associate professor of English at The University of Tampa, Florida. His interests cover the literature of the African imagination—literary expressions in the African continent as well as in the African Diaspora. So the Path Does not Die is his first novel. His short story "‘Foreign Aid" was on the shortlist for the 2013 Caine Prize for African Writing.

Vitabu: I found So the Path Does Not Die a remarkable book. The story travels from a graphic, mystical past to the present time, through almost impossible and sometimes hidden cultural, social and economic issues. How did you come up with the idea for the Musudugu chaper?

Pede Hollist: Among the Kuranko, Musudugu refers to a woman’s dwelling, but it also describes a mythical place where only women lived, happily and in sisterhood. The story of Kumba Kargbo’s confrontation with the elders of Musudugu suggests that the conflict between old and new ways and the tension between an individual’s desires and community needs go as far back as the earliest human communities; would have existed even in a mythical utopia like Musudugu, and are, in fact universal. Once that idea crystallized, I tried to evoke the sense of a far off time and place by mimicking oral storytelling through the language.

Vitabu: In the moving prologue, you explore hierarchies set in an indigenous African village, before the story segues into the eponymous struggle and follows the trail to the end. But I had a sense of inevitability almost. Does the past always come back with some vengeance as one follows a dream?

Pede Hollist: The past accounts for our present and is always with us. If we are conscious of how it inhabits our current circumstances, we can limit how it affects our future. When we are not, it appears to come back with vengeance.

Vitabu: I also found a lot of poignancy in So the Path Does Not Die. Probably because, on a personal level, I saw a portrait of women and girls in the Freetown I grew up in. On a more general level, the reader comes across many familiar faces and stories of poverty situated in urban Africa.

For Amadu, it meant choosing to not go to hospital to avoid losing his job and the additional income it generated. For Nabou, Amadu's widow, it meant that to hold up the family left behind (her and daughters Finaba and baby Isa) she had to voluntarily place Fina in foster care with the Heddles. Because she could not afford to send Fina to school. Nabou herself had been taken out of school to marry Amadu. After his death, her petty trade selling boiled eggs, oranges, cigarettes and mints (the profits of which she had enrolled Fina in school and cooked meals for the family) was hardly enough to provide for their basic needs and create opportunity.

Poverty means making stark choices. What you call "enduring the pain, sacrificing a little of the body so that much will be gained."

Fina cries her heart out in a number of scenes and you can't help agonizing over the beating she got from Heddle. A lot of raw emotion made even more painful because Fina doesn't yell or get angry. And there's the powerful, moving scene in the shower. Later, her guardian manipulates his ward into luring adolescent school friends who he plies with money for sexual favors. For Nabou, the final outcome isn't about the pain her daughter has to endure but who her daughter can be.

"You have food to eat, a bed to sleep in, and a light to read by. That's what is important. Stay there for now. Finish school! Go to college! After that you can do whatever you want." pp 30

I found the first part of So the Path Does Not Die a good look at the lives of women and girls: economic insecurity, education (or the lack of), health and well being, violence, safety (sexual predators Heddle and the lab attendant) and about giving back or expectations. Can you comment on your experiences in relation to all this?

Pede Hollist: Many years ago when I enrolled my daughters in a private school in the U.S., I found out that they did not have as many extra-curricular sports options as the boys but were required to pay the same fees. I brought this up with the school’s principal. I don’t exactly remember his response, but it was in the order of, this is the way things are.

Perhaps motivated more by economic unfairness than moral outrage or gender inequality, I began to carefully look at the status of women in a range of fields and activities. Inequity is structural, built in any number of ways into the fabric of our lives so that it appears normal. Women and men participate in that inequity, some consciously but mostly unconsciously.

As I look back at my child and young adulthood, and even now, I can see how the matrix of inequity is not only structural but can be trans generational, how I participate in it, and how, as a man, I am often a beneficiary of it.

So when Nabou is taken out of school to get married, the decision effectively closes off a number of educational and economic opportunities (and their attendant independence) for her. Unless she is conscious of that past, which she is, its limitations will be passed on to Fina. And, indeed, they are when the family finds itself in Freetown. Unskilled and widowed, Nabou is forced to hand Fina over to another family in order for the child to get an education. The image of Fina entering her foster family’s house through the back door symbolizes the disadvantaged position from which she starts. Her ethnic, regional, and religious backgrounds, and when she gets to the U.S., national origin, provide additional areas in which structural inequities play themselves out.

Vitabu: The second half is set in America with all the problems of the lives of immigrants and a cross-cultural romance. But the complications are there from the get go. Is everyone a "mere cog in the design which had been mapped out earlier"?

Pede Hollist: No, we are born into socio-economic and historical realities which we can either recognize as man-made and therefore within our control to change or accept them as divine-constructed, unchangeable, and therefore outside our control. Depending on our understanding of our reality, we can become mere cogs, passive and unthinking, sustaining or being sustained by the status quo like Ade, or we can become active and critical, agitating against the status quo, becoming, or thrust into becoming, a gadfly of sorts, like Fina. Of course, these are not exclusive or absolute categories we are locked into for all our lives. Depending on personality and life circumstances, we are sometimes cogs because we benefit from the status quo. When we don’t benefit, we can, if we summon the strength, become agitators.

So the Path Does Not Die

Publisher: Langaa RPCIG Cameroon

ISBN: 9789956727377 296 pages

Comments

Post a Comment